Dressed in dark colours and a black baseball cap, in person the 55-year-old Steve Buscemi cuts basically the same slight, rumpled figure we met a quarter-century ago in Jim Jarmusch's Mystery Train. He might be a roadie coming off a world tour. His famously exophthalmic eyes are a washed-out blue and he's tired, back home in Brooklyn after staying at his house in upstate New York. He likes to go there and hang out and do nothing, he says, maybe take a walk or do a bit of yardwork: he spent the weekend raking leaves. Self-effacing, friendly, polite, it's clear he's here under low-grade sufferance; interviews, he says in his quick, metallic, slightly strangulated way, "aren't my favourite thing to do".

He is a patient but mildly reluctant witness to his own life, but when the conversation turns to politics – with the Senate still days away from reaching a deal on the government shutdown – the reticence dissolves.

"I think the shutdown is ridiculous. I think the Republicans in Congress are holding the country hostage. I think it's criminal. I don't see why they're allowed to do it." Buscemi on politics livens up. "The Tea Party faction of the Republican party are holding the Republican party hostage. They've hijacked it. I don't understand their philosophy. I think that in their own hearts and minds there's a reason why they feel they're doing good. But I certainly don't agree with it. And I hope the shutdown effects change. I hope people remember this in the next cycle of elections."

If he expresses himself like that rare bird, the blue-collar liberal, it's no performance. He grew up five miles east of Park Slope, where we meet at a diner near his house, in a part he describes as "pretty far out, pretty deep into Brooklyn". There were six of them in a one-bedroom apartment: his parents slept on a sofa in the living room. His dad worked for the sanitation department and his mother gave up work as a waitress to look after their four boys. Steve is the second eldest: his older brother Jon is a cable guy for Time Warner, Michael is an actor and Kenneth, the youngest, works for the transit authority on the tracks. Buscemi says he was "always interested in acting", but "didn't feel that connected to the drama department. I felt more comfortable around jocks." But in his senior year at high school an English teacher, Mr Lynne Lappin, started a drama group, and Buscemi started auditioning for school plays. When he was 17, his class did a production of West Side Story, and "that was the first role I played, Baby John, the youngest member of the Jets".

After high school, he studied liberal arts at Nassau community college, dropping out after one term: "I wasn't taking any theatre, I wasn't doing any sports, it just seemed like I wasn't doing anything that was going to be useful." Various dead-end jobs followed: "gas-station attendant and dishwasher and I drove an ice-cream van" (experience he would mine for his understated and influential 1997 directorial debut, Trees Lounge). Keen for his sons to have steady jobs, his father persuaded him to take the local civil service exam and he applied for the fire service. He passed, but knew it would be a few years before his name came to the top of the list. He figured he had some time to see if the acting or the standup would come to anything. A childhood accident (when he was four he was hit by a bus, fracturing his skull) resulted in compensation many years later, and the cash helped him "to go to the Lee Strasberg school and take acting classes. It seemed to be the logical thing to do."

Attending the school, and commuting from Long Island into the city, was "a big adventure, a big endeavour" and "quite intimidating for me. I didn't know the city at all. It was pretty overwhelming." After finishing at the Lee Strasberg school, he started taking classes with John Strasberg, Lee's son, and in 1978 he moved into the East Village, then the hub of New York City's creativity, although Buscemi only lived there because it was cheap. "I had missed the beginnings of the Ramones, Talking Heads and Blondie because that was a little bit earlier, but I had no idea of the scene that was happening. I mean, I sort of knew but didn't feel connected to it." To pay his bills, he worked as a furniture mover and a busboy. Since he had no agent, he found auditions only by "combing the back pages of the trade papers for student films or big casting calls. I went on a huge casting call for the movie Fame and lasted," he laughs, "less than 30 seconds. And I don't think Alan Parker was even in the room."

Buscemi was influenced by comics such as Freddie Prinze, George Carlin and Steve Martin, and hung out at the Improv, a midtown comedy club where he watched contemporaries such as Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David hitting their stride. (One night Andy Kaufman got Buscemi and his friends up on stage, to accompany him in a rendition of Old MacDonald Had a Farm, assigning each of them an animal.) In his own standup he did mostly observational humour but he was, he says, too young to be doing it. "There were guys like Prinze, who was on the Johnny Carson show when he was 17, but he had lived a life." Buscemi's existence was suspended in some regards: he has talked before of not having a girlfriend until he was 22, the same age he finally joined the fire department. Working as a firefighter during the day, on engine 55 in Little Italy, Buscemi would appear on the bills of comedy clubs uptown at night.

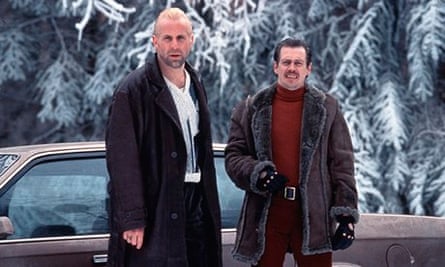

In 1982, he met Mark Boone Junior (who now stars in the show Sons of Anarchy) and they formed a comedy partnership; in contemporaneous photos Buscemi and Boone look like Laurel and Hardy as styled by Gap. "Mr Buscemi is a thin-skinned ectomorph continually menaced by Mr Boone's roly-poly endomorph," came the review from the New York Times in 1988. "In their best performance pieces, the two ritualistically parody male power struggles as an ongoing clash between these opposite, mutually suspicious types." They stayed together for eight years, performing improv and sketches until Boone moved to LA in 1990.

Meanwhile, Buscemi's solo career started and stopped. He received good reviews for his role of Nick, a gay man dying of Aids, in the low-budget Parting Glances in 1986, and by the end of the shoot, he had taken a three-month leave of absence from fire fighting, which he kept extending until he just never returned. This clearly still pains him, and he stresses: "I had planned on going back." (The day after 9/11, Buscemi went down to Ground Zero and walked around until he found his old company, engine 55, and dug rubble with them. "For the next four or five days I would just show up and work with them. They'd lost five members – one of them I'd worked with.")

In 1988, he says he had his best experience as an actor, making the influential Mystery Train with Jim Jarmusch: "Just being in Memphis, in the summer, shooting at night and getting to work with Joe Strummer and Rick Aviles, a standup who I admired. I used to see Aviles doing his comedy in Washington Square Park in the late 70s. He was really funny." From Jarmusch, and Alexandre Rockwell, who directed him in In the Soup, and Tom DiCillo, his director in Living in Oblivion, Buscemi learned some of his own directing techniques; using rehearsals and improvising outside of a script. All of them, he says, came out of the "East Village sensibility", and when he worked with those directors, "it felt like you were really trying to make something".

Buscemi himself has directed a little in television (including Pine Barrens, one of the finest episodes of The Sopranos), plus four movies, the last of which, 2007's Interview, was a remake of a movie by Theo Van Gogh – the Dutch film-maker who made Submission, about women in Islam, and was murdered by a Dutch-Moroccan Muslim in 2004. Buscemi plays an embittered political journalist forced to interview Sienna Miller's soap star, and it's a very tight, very caustic two-hander with some startling reversals.

Embittered is a word that comes up often when you think about Buscemi's characters. Even his actual physical presence onscreen is edgy. The eyes dart and the whole skinny body bristles, ready to respond to some slight or threat, perceived or real. His characters are frequently touchy, olympic-class complainers. One thinks of Mr Pink in Reservoir Dogs, or the kidnapper-turned-murderer Carl Showalter in the Coen brother's Fargo, or Seymour in Terry Zwigoff's Ghost World, all men constantly riled by circumstance.

After Reservoir Dogs in 1992, Buscemi shelved any notions of following Boone westward to Hollywood: he was now in demand enough for Hollywood to come to him. Roles in major blockbusters followed – Con Air, Armageddon – and he has never stopped working, making more than a hundred movies, with everyone from Michael Bay to Tim Burton. (He doesn't differentiate between indie movies and blockbusters, except that he doesn't like the fact that large movies tend to have more "waiting around and 'piecemealing' it together".) He pops up in six of the Coen brothers' movies, and in several of Adam Sandler's, including a memorable turn as a rancorous drunk in The Wedding Singer (his best-man speech concludes: "I'm a person, too. Goddamn it, I'm a person too").

Almost despite himself, there is something people-pleasing about Buscemi. In interviews his father has talked about "the Buscemi temper" – his own – and the son seems like an exasperated peacemaker. As the second of four brothers, you can guess that he has learned to mediate. It's indicative of a Buscemi character that though he may be morally compromised – by anything from pedantry to murder – the viewer recognises the character's conflicting impulses both to stand up for themselves and smooth everything over.

And yet, as a former high school wrestler, he is clearly not afraid of confrontation. He sighs enormously when I ask him about it, but he dutifully recalls the story of getting stabbed in a bar when filming with Vince Vaughn in Wilmington, North Carolina: "We were out, we were in a bar, there was some trouble between Vince and another guy and that was taped, so they went outside but that was broken up, and we were actually just trying to leave, and then somebody else just started saying something and I had words with him and he pulled out a knife, and we sort of wrestled around and I got the worst of it." The worst of it was being stabbed in the head, throat and arm. Buscemi says "everybody was drinking too much and I don't know what else he was doing that may have caused him to go into a semi-psychotic state". A witness reported the fight began after Vaughn talked to the girlfriend of a local man, Timothy Fogerty. Fogerty was charged with assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill. When I ask Buscemi what movie they were filming down in North Carolina, he pauses for a long time and looks at the table. "I'll think of it in a minute." (Domestic Disturbance: I looked it up.)

Buscemi says he has never felt typecast, and rejects the lazy assertion that all his characters are weirdos and losers. "I don't know if they're likable but they're human." Still, there's no denying that Boardwalk Empire, the new series of which we're ostensibly here to talk about, is a change of pace: a lead role in a TV show. The character actor who specialised in the slightly off-key is now the main man. Nucky Thompson is based on Enoch Johnson, a real-life Atlantic City politician turned criminal kingpin, and several other real characters weave in and out of the narrative: Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, Bugsy Siegel and even, in the latest series, J Edgar Hoover. The show, a glossy epic of sex, intrigue and a great deal of violence, details how prohibition gave birth to organised crime: the first Scorsese-directed episode came in at $18m (the most expensive in TV history), with a replica of the Atlantic City boardwalk, reconstructed in Brooklyn, costing $5m alone.

As soon as he read the script, Buscemi knew he wanted the part. "I don't know if he's a good guy. He's a politician. I think he's smart, a smart businessman, and if he can avoid violence that's his first choice." As Thompson says in the show, until prohibition "I was a run of the mill crook, a corrupt city official and I was happy. Plenty of money, plenty of friends, plenty of everything. But then suddenly plenty wasn't enough." Buscemi plays Thompson as a kind of anti-type of the mob boss. He has a gift for strategy and persistence but he's not domineering or a natural leader. He's also happy enough to have people killed, or when he deems it necessary kill them himself. And yet Buscemi manages to impart a dignity and forbearance to the character. Thompson takes little pleasure in his pleasures and yet he has this overwhelming ambition to stay at the top of the tree.

In Boardwalk, money is king, and a Randian philosophy pervades. Buscemi himself is more reasonable. "I'm not against capitalism, but it's another thing to blame the victim. A lot of poor people have made something of themselves but nobody does it on their own. Everybody needs help. There's nothing wrong with having government help, and I think if your goal is only to make money, that's not a worthy goal in and of itself." Though he admires the fact that Michael Bloomberg, New York's mayor, doesn't have to rely on anyone for money, and so has been able to take strong positions on issues such as gun control, he is less enamoured with his philosophy of making the city attractive to billionaires. "The idea that the money would trickle down to the poor is condescending, and doesn't work."

Buscemi laments that "so many working-class people across the country vote against their own interests. It all comes down to culture wars: the right has always been able to use abortion and gay marriage, and in the past women's rights, but all those things are starting to erode. There really isn't much they can throw up as a smokescreen any more." I ask him about gun control (for), fracking (against), Obama (a little disappointed), the Keystone pipeline (against), stop and frisk (racist), progressive taxation (for) … and it's apparent we could keep talking politics for some time quite happily. Suddenly he's in the skin of one of his characters, animated by contempt, needled by the world.

Boardwalk Empire returns to Sky Atlantic HD on Saturday 26 October at 9pm

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion