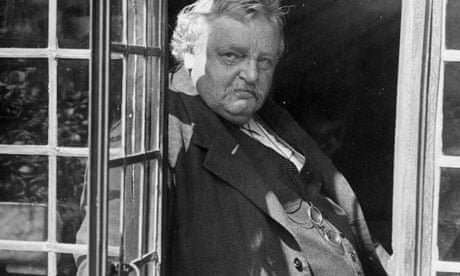

There was never just one GK Chesterton. There was Chesterton the Catholic proselytiser, the hearty balladeer of Merrie England, the harrumphing castigator of teetotallers and vegetarians, the blustery anti-Communist, anti-plutocrat and, also, alas, anti-Semite. There was Chesterton the charmer of children - one little boy, asked after a visit to the great man's home if GKC had been awfully clever, replied, "I don't know about clever, but you should see him catch buns in his mouf." There was Chesterton the week-in-week-out jobbing journalist, producing essays on every subject under the sun, whether it be the intellectual inferiority of MPs to the populace they are elected to serve ("the blind leading the people who can see") or what he regarded as the inherent contrariness of feminism ("women asserted that they would not be dictated to, but then became stenographers"). There was Chesterton the polemicist, eternally twinned, like a pantomime horse, with his close friend and sparring partner, Hilaire Belloc. There was Chesterton the aphorist and Chesterton the metaphorist. There was the Chesterton who employed paradoxes (the feeblest of which were little more than platitudes performing handstands, while the best were as brilliant as Wilde's) with the same relish and frequency that contemporary writers use when employing swear words. And there was, supremely, Chesterton the deviser of the craftiest detective stories in the English language (nine-tenths of his writings are currently out of print).

The most popular of these stories remain, of course, the ones featuring Father Brown, but Chesterton had lots of others published, either in magazines or between hard covers. He wasn't one of those writers constrained by material imperatives to expend his quotidian energy on what he secretly repudiated as hack work, while dreaming of the masterpieces he would create if only he had the time. He took the detective story seriously enough to write a sprightly defence of the genre and was, alongside Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Anthony Berkeley et al, an assiduous member of the Detection Club. It's hard to believe he would have been aghast to discover that, if his name is still a conjurable one, it's almost exclusively because of his mystery fiction.

The six episodes of The Club of Queer Trades (a title that, in this less innocent century of ours, would carry a rather ambiguous connotation) are not, strictly, detective stories, and they are certainly not mini-whodunnits. What interested Chesterton was not the least likely suspect but the least likely motive. Their basic structure, however, is exactly comparable to those of the Father Brown adventures. A quite impossible effect is described, only to be shown, with a climactic flourish, to have had a perfectly possible cause all along. In the fourth story, "The Singular Speculation of the House-Agent", Chesterton's protagonist and alter ego (or alter egoist), Basil Grant, a whimsical judge-turned-flâneur, remarks, "Truth must of necessity be stranger than fiction, for fiction is the creation of the human mind, and therefore is congenial to it." If, as one assumes, it is Chesterton himself who is speaking through Grant, then it was patently his ambition, in all of his shorter texts, to write fiction that would turn out to be stranger than truth.

Chesterton sought always to entertain - he was a reader's writer rather than a writer's writer. Yet even these light-textured tales (the members of the titular club must each practise a heretofore unheard-of profession) have, as is often the case with this author, a profoundly unsettling undertow. The Argentinian fabulist Jorge Luis Borges, a great admirer, once made an intriguing claim. He said that, while Dickens' fiction piled on the agonies of poverty, neglect, violence, solitude and death, the warmth of his style guaranteed that the society he depicted never ceased to be convivial. The ostensibly breezy, life-loving Chesterton, by contrast, tended to write nightmarish fictions full of ominously lurid sunsets and wild-eyed, red-haired young poets. Red hair, in fact, might be what semiologists term the trivial signifier of his entire imaginative world. Amazingly, no fewer than three of the characters in The Club of Queer Trades are red-haired, in just six stories, and on each occasion, given the eerie atmospherics, one cannot help visualising that hair as literally red, practically blood-red.

Even if, in Chesterton's work, crimes that seem to be rooted in the pagan and the supernatural are invariably revealed, come the dénouement, to have had a reassuringly rational basis, an aftertaste of occult perversity lingers, as it does from a proper nightmare. In short, the more one reads him, the more one begins to wonder whether this jolly, God-fearing man might just have been, in today's vulgar parlance, sick. It is, at any rate, his flesh-creeping proximity to Poe and Kafka and indeed Borges that makes him not just still readable but still curiously modern.

Consider this passage from "The Eccentric Seclusion of the Old Lady":

We were walking along a lonely terrace in Brompton together. The street was full of that bright blue twilight which comes about half past eight in summer, and which seems for the moment to be not so much a coming of darkness as the turning on of a new azure illuminator, as if the earth were lit suddenly by a sapphire sun. In the cool blue the lemon tint of the lamps had already begun to flame.

A sapphire sun! And not in Benares, mind you, but in Brompton! Chesterton was incapable of writing about humdrum old London without exoticising it and, though he may well never even have heard of Magritte, it is of Magritte's topsy-turvy nightscapes that one thinks when reading passages such as these (of which there are many in his work). Thus, congenitally hostile to all isms as he was, save of course for Catholicism, he himself proved to be something of a Surrealist avant la lettre. And that, perhaps, was the crowning paradox of GK Chesterton.

· The Club of Queer Trades is reissued this month by Hesperus Press.