Andrew Nagorski, author of the new book Hitlerland, discusses the way Americans saw -- and wrote about -- the early days of the Third Reich.

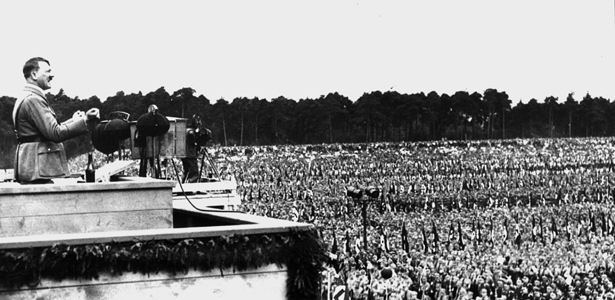

AP Images

What did Americans think of Hitler when they first met him in the 1920s and 1930s? You write that some of them burst out laughing at his shrill voice and jerky hand movements and refused to take him seriously.

That's true. In fact, some of the first people who met him did take him quite seriously. Truman Smith, who was a junior military attaché in the 1920s, came away from meeting Hitler and said, "This is a marvelous demagogue who can really inspire loyalty." It was the same with Karl von Wiegand, a Hearst correspondent who was the first American journalist to interview Hitler back in 1922. He was struck by Hitler's oratorical skills and his ability to whip people into a frenzy.

Then you had this period after the Beer Hall Putsch where Hitler came out of prison and a lot of people had forgotten about him. After the Great Depression hit, suddenly the Nazi Party became a major contender for power. Yet you had Americans meeting Hitler and saying, "This guy is a clown. He's like a caricature of himself." And a lot of them went through this whole litany about how even if Hitler got into a position of power, other German politicians would somehow be able to control him. A lot of German politicians believed this themselves.

Of course, everyone began to reassess that very quickly after he took power. But some of the Americans were much more prescient -- for instance, Edgar Mowrer, the Chicago Daily News correspondent, kept frantically trying to warn readers and the world, "What he's saying about the Jews is serious. Don't underestimate him."

How hard did these writers work to find out what was really going on? Did they take risks to get to the real story, or were they mostly content to stay in their comfortable bubble?

When you're a foreign correspondent, there's always the possibility of staying in your own little world. You all go over to each other's houses, you entertain each other, you have expense accounts. And the American correspondents and diplomats in Berlin were living in relative luxury. Even so, the good correspondents and diplomats did go out and seek information, even when it became progressively more difficult -- and more dangerous -- to get it.

That's what I found really interesting in a case like Edgar Mowrer, how he'd get information from a German-Jewish doctor. He'd make appointments to see him very often. The doctor would make sure his assistant was out of the room, and then he'd slip a note into Mowrer's shirt with information about who had been arrested, what had happened. When even that became too dangerous, Mowrer started a ritual of meeting the doctor at a public toilet once a week. They'd stand at neighboring urinals, and before each of them left, the doctor would drop that little sheet of paper, which Mowrer would pick up. Then they'd leave through separate exits.

Some journalists and diplomats took those kinds of risks and really pushed to get everything. Others held back -- after all, Germany really was a very prestigious reporting assignment. They felt constrained and didn't want to jeopardize their situation.

Was there an appetite for this news back home?

On the part of the newspaper editors, there was some skepticism about the early stories. In World War I, American newspapers had published a lot of stories about German atrocities -- about how they were bayoneting babies in Belgium -- and those proved to be fabrications. So I think the editors were open to some of these first reports about the Nazis, but they were wary.

Even the reporters were sometimes slow to write about the things they witnessed firsthand. I tell the story of Hans Kaltenborn, a famous radio broadcaster of that era. He was of German descent, but had grown up in the United States. Right after Hitler took power, there were attacks on Americans who failed to give the Hitler salute. Kaltenborn went over with the attitude that these reports were greatly exaggerated. Then his teenage son got beaten up for exactly the same reason. The Nazis apologized profusely and said, "I hope you won't write about this." And Kaltenborn replied, "No, I don't insert anything personal in my stories." Even after this happened to his own son, he was reluctant to write about it.

Talk a bit about the Lindbergs. Their sympathy with Hitler is famous now, but you have a slightly different take on it.

The Lindbergs were definitely among the American people who tried to say, "Hitler is bringing Germany back to its feet. Look how orderly this place is now." But what I found really interesting was that Charles Lindberg played another role: He provided real-time intelligence for United States.

In 1936, Truman Smith, the military attaché, was trying to report on the military buildup under Hitler, but he had very little information about the air force. He saw a Herald Tribune article about how Lindberg had toured French airplane factories and military facilities. So he suggested to the German air ministry that they invite Lindberg over as a guest.

Sure enough, once Lindberg got there, the Germans wanted to show off everything to him. They took him to the factories that were producing the most modern fighters and bombers. Lindberg really knew his stuff, so he could turn to the American diplomats next to him and say, "This one is more advanced than French model but less advanced than American model."

He played this role very willingly, knowing this intelligence was being transmitted to Washington -- probably because he thought the more his government knew about the power of these weapons, the less likely they'd be to get involved in another war. He later became part of the America First movement, which tried to keep America out of war at all costs. But he provided valuable intelligence. For me, that was the most interesting part of the story.

Lindberg was also notoriously anti-Semitic -- and so were a lot of other Americans at that time. Did that make it easier for American journalists and diplomats in Germany to brush off the warning signs they saw?

Sure. When the controversy over the 1936 Berlin Olympics took place, one of the American Olympic Committee members who went to check out the place said at a certain point, "Well, my men's club in Chicago won't accept Jews either." So there was a kind of camaraderie there, a sense of, "Ho, ho -- we all do that."

But wasn't it obvious from Mein Kampf and Hitler's early speeches that he had something more sinister in mind than a gentleman's agreement?

If you look back to the very beginning of Hitler's rhetoric about Jews, it was all there -- the talk about extermination and vermin. He didn't spell out exactly what would happen in the Holocaust, but he gave a pretty good indication of its overall thrust. When someone lobs those kinds of rhetorical bombs, it's sort of a natural human tendency to say, "Oh, that's just a figure of speech. They don't really mean it. It's just a way to whip up supporters."

But at a certain point, people began to witness things that were unbelievably horrifying. And of course, there was Kristallnacht. After that, even the people who at first wanted to dismiss every incident as local people getting out of control began to take the problem seriously. There's quite a difference between being socially anti-Semitic and seeing people beaten on the streets.

Even the German Jews didn't seem to realize the danger they were facing. It's interesting to see that the American journalists were sometimes the first ones to warn them about it.

Yes. Edgar Mowrer, the Chicago Daily News correspondent who was basically run out of Germany in September of 1933, kept advising Jews, "Get out of Germany!" There's a scene in the book where Mowrer is having lunch with group of Jewish bankers in Germany, and it becomes clear that each of them has given some money to Nazi Party at the urging of non-Jewish industrialists. They were told it would be a way of protecting themselves a bit, and they believed it. Just like a lot of Americans, the German Jews thought, "This can't really be happening."

But one of the things I found fascinating in writing this book was to put myself in the shoes of the people there, who didn't have the benefit of hindsight, and wonder, 'What would I have understood? What would I have done?" I came away from it all knowing that I couldn't, with any assurance, say I would have been any smarter.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.