WEAPONS OF WAR

This Armstrong behemoth was unusual not just for its size, but also for its innovative automation.

During the second half of the 19th century, an arms race was afoot. Britain, France and Germany had wary eyes on one another, while an emergent Italy thrust itself into war with Austria-Hungary.

In a time of industrial innovation and imperial expansion, the capital warship was arguably at the apex of its relative power. Steam and iron replaced wood and sail, and as technology caught up with ambition Europe’s navies firmly believed – when it came to guns at least – that bigger was better.

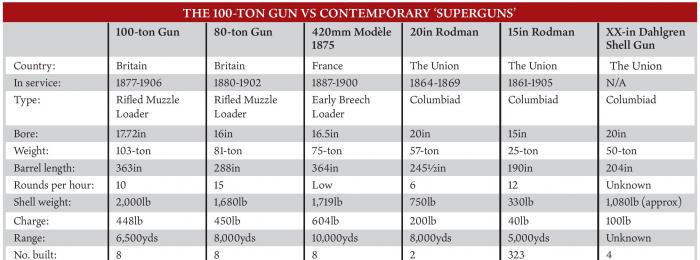

One of the largest guns of the time, the 12.5in RML (Rifled Muzzle Loader) entered Royal Navy service in the 1870s. The 16½ft long, 38-ton cannon were capable of piercing 16in of armour plate at a distance of a mile, throwing 800lb shells out to 6,000 yards. In 1877, the French began construction of the four ironclads of the Terribleclass. They’d take a decade to complete, but each carried a pair of the largest calibre guns ever mounted to a French warship: 75-ton 420mm (16.5in) weapons that dwarfed any comparable arm.

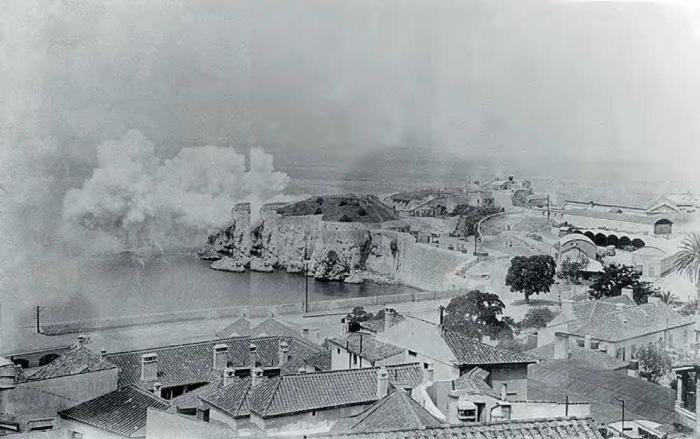

At the Royal Navy’s behest, the Royal Gun Factory began designing an 80-ton-gun – the 16in RML produced by the Royal Arsenal – costing around £10,000 (£1.21m today) each. These saw action during the 1882 bombardment of Alexandria and could fire a 1,700lb shell for 8,000 yards. Just eight of them were built, with HMS Inflexible the only ship to mount them. Two were emplaced in Dover Harbour, Kent, where their rusted remains can still be found (although they are inaccessible to the public).

Arming a rival

An altogether larger beast was being developed by the Elswick Ordnance Company, the armaments division of Armstrong Mitchell & Company (later Armstrong Whitworth). The firm’s RML 17.72in – the 100-ton gun – was and remains the largest muzzle-loading cannon to ever be produced.

Initially, 11 were ordered, but they were not destined for British service, being rejected due to their weight and expense, each costing £16,000 (£1.87m today). Instead, they went to rival Italy, where Risorgimento (resurgence/ unification) had culminated in a united kingdom. Decades of turmoil saw Sardinia and Sicily (which held much of north and south Italy respectively) and the central provinces unite under proclamation in 1861. By 1871, Rome had become Italy’s capital following the annexation of the Papal State and much of the remaining free territories on the peninsula.

“Elswick Ordnance’s RML 17.72in was and remains the largest muzzle-loading cannon ever produced”

The newly established Regia Marina had great ambitions. The merger of the Neapolitan, Sardinian and other fleets in 1861 meant Italy had inherited a large naval force, but it was a mixed bag when it came to technology, ability and tradition. War with Austria resulted in the fledging Italian navy being roundly defeated at Lissa in July 1866. Modernisation, streamlining and greater cohesion were needed at a time of rapid advancement. Leadership had to change and Italy had to acquire the infrastructure to produce modern ships.

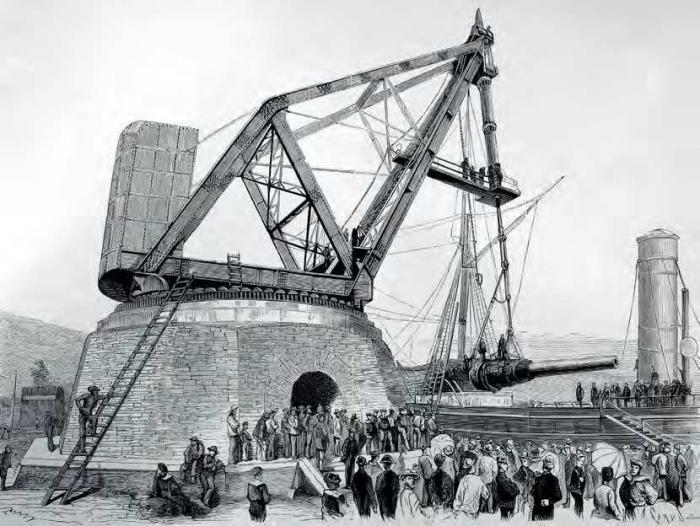

It embarked on a rapid programme of expansion to develop a formidable regional force. Its first modern ironclads were the Caio Duilio-class, two innovative ships designed to carry the most powerful armament available. Following negotiations with Armstrong in 1874, it was agreed both would carry the 100-ton gun. Three more were ordered, one as a coastal gun at La Spezia and two as spares. Engravings and drawings of the guns being unloaded at Spezia and installed on the Duilio ran in the Illustrated London News in 1876, with that publication and the Scientific American running articles on the Newcastle-made monster.

Threat to Malta

The purchase of the 100-ton gun caused ripples. Malta, a vital way station, came under British control in 1814, but once the Suez Canal was opened in 1869 it became the most important strategic holding in the world. Located midway between Gibraltar and the canal’s entrance, Malta was uniquely positioned to dominate and control the Mediterranean and one of the world’s busiest trade routes.

However, Sicily was only 60 miles across the water and major Italian naval bases weren’t much further away. ‘Irredentismo’, a prominent nationalist concept that believed in the unification of provinces it identified as being indigenously Italian, extended into the upper echelons of society, its backers including reformist strongman and future prime minister Francesco Crispi. The Irredentists considered Dalmatia and Nice to be ‘unredeemed’ Italy, and believed Malta should fall within the kingdom.

Three centuries of Hospitaller, French and British rule had seen awesome fortifications established on the island stronghold, but the 100-ton gun allowed the new ironclads to blast Malta’s batteries at arm’s length. The guns outranged the 12.5in types forming the island’s toughest defences, although the well-armoured ironclads were near-immune to return fire anyway. Subsequent Italian capital ships also mounted similarly large guns.

Malta and Gibraltar required up-gunning and designs for new cannon were developed, some more than twice as heavy as the 100-ton gun and the largest weighing as much as a small warship (approximately 260-300 tons). These ambitious projects would take time to develop and anything larger than Elswick’s monster would be too unwieldy.

In 1875, Sir John Linton Simmons, a future governor of Malta who had advised Ottoman forces in the Crimean War, was made Inspector General of Fortifications. He became part of a royal commission investigating defences in empire holdings and, in December 1877, requested a quartet of guns for Malta comparable to those sold to the Italians. Noting that shore batteries had an advantage over equivalent naval guns, it was decided to order four 100-ton guns.

Building a giant

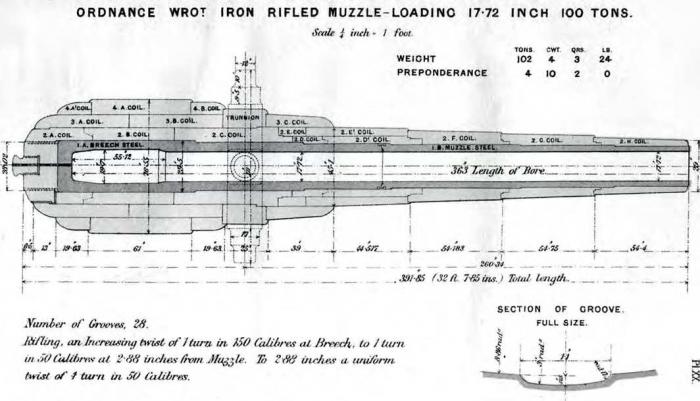

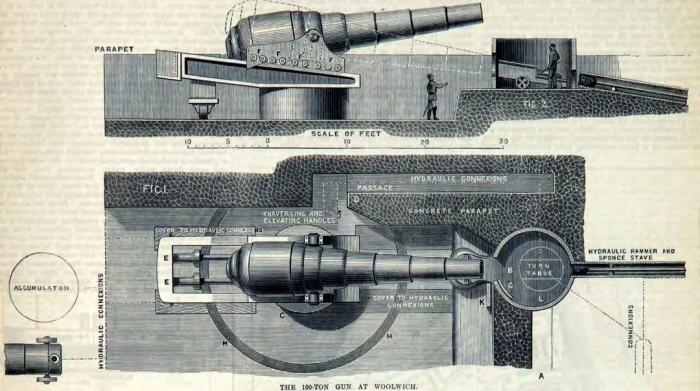

The 100-ton gun is a rifled muzzle-loading Armstrongtype cannon measuring 32ft 7¾in long. Although today it appears primitive, it was a staggering technical achievement.

The gun measured 61in in diameter at its thickest and 20in at the muzzle. The barrel and chamber were forged steel, the latter 55in long and 19¾in in diameter, while the barrel was 30ft 3in long and the inner bore 17.72in. Both were encased by 16 overlapping wrought iron tubes (heated and shrunk in place) and a trunnion. Over the chamber and the base of the barrel this compress was three layers thick, while one layer covered the forward third of the gun. This intricate construction not only gave Armstrong guns their distinctive appearance but enabled the 100-tonner to better withstand the tremendous pressures of firing.

“The armour-piercing Palliser shells could pierce 21in of steel at 2,000 yards, shattering the plate and scattering chunks weighing several tons ”

Up to four black powder charge bags, containing 1cwt (112lb) of propellent, were used to fire the 2,000lb shells and velocity at maximum charge was approximately 1,548ft/s. The armourpiercing Palliser shells (cast iron and steel tipped) could pierce 21in of steel at 2,000 yards, shattering the plate and scattering chunks weighing several tons. When fired at a ‘sandwich’ of two iron armour layers (12in and 10in thick) and two wood (12in and 16in) to simulate warship protection, the results were devastating. The hit left a 6ft hole and threw large splinters inward. A high-explosive shell containing a 78lb bursting charge also issued, while a shrapnel shell with more than 900 4oz pellets was produced, though it fell out of use.

From the late 1870s, gaschecks had been attached to shells to save barrel wear and increase accuracy and range, replacing the bronze studs previously used to impart spin. The 100-tonners required a 25lb automatic gas-check (so-named as it attached on firing) to force the shells to spin down the rifling. Few 17.72in gas-checks survive, as they remained with the shell in flight. Those escaping firing or scrapping were typically retrieved after a rare misfire.

Installing the superguns

Production of the British guns began in August 1878, but new guns also meant new fortifications. The two Malta batteries, Rinella and Cambridge, were built to the east (Kalkara) and west (Tigné Point) of the Grand Harbour’s entrance, with the latter costing almost £19,000. In Gibraltar, the guns were emplaced in the Victoria and Napier of Magdala batteries, both of which overlooked the Bay of Gibraltar; these much simpler batteries cost £35,700 combined.

The guns were mounted en barbette – a term referring to guns that fired over a parapet rather than through an opening in an enclosure – on 50-ton mountings on a 4° slope to reduce recoil. They were protected by a rampart of compacted earth and a concrete glacis. The defences covered the guns’ crews from direct fire, with the magazines protected by being underground. The Malta batteries emplaced the guns behind limestone and concrete in pentagonal-style forts that featured the typical all-round defences of the time, such as a bent entry gate and firing slits. Both were covered by stone revetments, but these were partially replaced by earthworks.

ARMSTRONG’S OTHER SUPERGUN

The advent of breech-loading led to ever larger naval guns being developed and Elswick continued to build them. In the late 1880s, the manufacturer’s BL 16.25in was then the largest gun in existence and is the second-largest British naval gun ever developed, smaller only than the 1915-designed Elswick BL 18in Mk.I.

In 1887 the 16.25in was the main attraction at a Newcastle exhibition marking Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee, the same year its designer, William Armstrong, became the first engineer to be granted a peerage. Known as the 111-ton gun, it was similar to other arms supplied to the Italians and the Royal Navy demanded parity. Although weight and barrel life were problems, the 43ft 8in gun was impressive, firing 1,800lb shells at 2,020ft/s out to 8 miles that could pierce 30½in of iron at 1,000yds. A dozen were built, with two each arming HMS Benbow, Victoria and Sans Pareil from 1888 to 1909.

Work on the Rinella battery began in 1878. Its gun arrived in September 1882, but it took more than 100 men 87 days to transport the giant to its mounting, it was operational by early 1884 and the fort complete two years later. Construction of Cambridge commenced at the same time, with the gun arriving in July 1883. It had been installed by February 1884 and the position completed by 1886. Both batteries held 100 shells in their magazines.

In Gibraltar, work began in December 1879. Both batteries were integrated into existing fortifications and did not require the ditches, counterscarps and caponiers needed in Malta. As at Malta, the guns arrived independently in December 1882 and March 1883, and it took 21 days to move the 100-ton gun to Victoria Battery. Napier’s story is similar, but it was located further up in the cliffs. The two Gibraltar guns were fired for the first time in 1884, but it would be five years before both were fully operational. The two batteries held 87 shells in their magazines.

19th century automation

The batteries containing these formidable Victorian superguns are remarkable for being the first defences in the British Empire built with considerable automation.

The guns were too heavy for it to be practical to lay them by hand, and such huge shells would demand a large crew and plenty of space to manually prepare the muzzleloader. Steam made the guns viable by powering traverse and elevation while the 1-ton shells were raised from the subterranean magazines by steam hoists, moved by cart and loaded by machine. The intricate system meant fewer men were needed to operate the guns and enabled a fire rate of one round every 4/6 minutes. On test shoots, Napier battery managed an incredible four rounds in 10 minutes, but this damaged the gun beyond repair.

Each battery had two mirrored systems, one on each side of the gun. A coal-fired steam engine powered the hydraulics and accumulator to traverse, elevate, wash-out and load the guns. It took three hours to build up the required 950psi but, once up to pressure, rapid rates of fire were attainable. Two manual pumps were installed as a reserve and could sustain a fire rate of four per hour. The innovations meant just 35-40 crewmembers were needed and the dual mechanism afforded each team more time in the exhausting process of moving the shells and charges.

“ Napier managed an incredible four rounds in 10 minutes, damaging the gun beyond repair”

After firing, the gun was traversed 90° and depressed so the muzzle met one of two access points in the emplacement, automatically pushing aside the armoured cover. A 60ft hydraulic ramrod extended to douse embers and wash-out the barrel. Meanwhile, the crew raised the powder from the magazine and placed it onto one of two carts. These were pushed on rails to where the shell and gas check would be raised. The muzzle was depressed further to the reloading port, draining the dousing water. The payload was raised to the embrasure by steam lift and inserted by a hydraulic rammer. The gun could then be returned and fired.

Technology had other implications, too. The guns could be fired electronically or even remotely, although lanyards were considered more reliable. With advances in communications, targeting information could be relayed by telephone from observers on higher ground. Inside the battery, commands were delivered though speaking tubes or loudhailer. Later, targeting information could be relayed to dials displaying bearing and elevation calculations from the rangefinders.

MALLET’S MORTARS

Another giant Victorian weapon, built in 1855 to breach Sevastopol, was designed by Irish engineer and geophysicist Robert Mallet. He devised the 42-ton Mallet’s Mortar, which had a 36in bore. Two were built and both survive in the Royal Armouries collection, with the example shown being at Fort Nelson in Portsmouth.

Each cost £4,300 and consisted of a cast iron baseplate, a wrought iron chamber and a barrel made from three wrought iron rings clamped by six longitudinal bolts. The mortar was mounted on a wooden platform, with thin wooden rings to act as shock absorbers. Mortars were originally siege weapons, and needed to launch bombs at high trajectories, Mallet’s design was no different and the elevation could be adjusted between 40° and 50°.

It was designed to be moved in sections. The yard-wide spherical shells contained a 480lb charge and weighed a ton, so had to be loaded by crane. A fire rate of 4 rounds per hour was attained and maximum range gauged at 2,750 yards with a 80lb charge. However, testing revealed several defects and sheared one of the bolts. And the end of the Crimean War meant these earth-moving mortars were never fired in anger. Mallet’s other work included Fastnet Rock lighthouse off Cape Clear, Co Cork. He is recognised as a leading pioneer in earthquake research and is attributed with coining the terms ‘epicentre’ and ‘seismology’.

Age of innovation

While this was an age of innovation, it was still a time without spotter aircraft or advanced fire-direction, so range was limited and poor weather conditions and the smoke from firing were obstacles to accuracy.

The guns were originally aimed by optical systems, but rangefinders were later mounted nearby. Even then, range was only as far as could be seen – roughly 6-8 miles. Accuracy and penetration would be reduced at that distance, so the guns were effective to about 4-5 miles or, officially, 6,500 yards (3¾miles).

Expense was another concern. The barrels wore out after 120 shots despite using gas-checks, and it was not feasible to dismount them for relining. In peacetime, batteries were limited to four rounds a year. Each firing cost £100, enough to pay the daily wage of 2,400 British soldiers.

War between Italy and Britain would not break out at this time. The Royal Navy’s dominance of the Mediterranean remained beyond the capabilities of the Regia Marina to challenge until the 1930s. However, Italy actively pursued territorial expansion and, for all that time, the 100-ton guns maintained watch.

The Cambridge gun was last fired in 1904 and scrapped in the 1950s. The area has since been redeveloped, but it is planned to restore surviving parts of the battery. Rinella escaped scrapping as it was in military use until 1965. Although its gun was long obsolete, the emplacement was a useful observation post for Fort Ricasoli. As Rinella became overgrown, it blended into its surroundings, which made it useful as a camouflaged storage facility. In the 1990s, it was passed to the Malta Heritage Trust and opened as a museum. The gun can be fired and work to restore its steam-powered loading system is ongoing. The wearing out of the Napier gun saw the one housed in Victoria moved up. Plans to fill the gap with long-range 9in types were never enacted and the battery became home to the Gibraltar Fire Station in the 1930s, with the fortification’s network of passageways still used for training. Napier continued in military use, notably as a site for 3.7in anti-aircraft guns during World War Two. ‘Rockbuster’, as its 100-tonner was nicknamed, was last fired ceremonially in 2002.

What was briefly the pinnacle of heavy gun design was outpaced by advances in propellants, metallurgy and fire control. Nevertheless, Victorian innovation had enabled a small crew to fire such a large gun at a fearsome rate. Britain’s mighty Mediterranean bastions never fired in anger, but, testament to their size and power, they were never challenged.

Next Month

The demands of the longrunning counter-insurgency campaign in Afghanistan led the British military procure a huge range of specialist vehicles chiefly intended to provide crews with protected mobility and firepower. Next month we profile the British Army’s modern, lightweight scout, patrol and fire support vehicle, the Supacat/SC Group Jackal MWMIK.