Valerio Olgiati’s remote Portuguese villa is a melancholy pleasure dome − an ark for two modelled on the Alhambra Palace

Wary of attracting unwanted visitors, Valerio Olgiati has asked me to exercise discretion in identifying the location of the Villa Além, the house that he has built in rural Portugal for his and his wife, Tamara’s, own use. While happy to oblige, I am not sure that he has much to worry about. I followed his instructions to a village situated an 80-minute drive south of Lisbon easily enough but then found myself having to navigate the final four kilometres by way of a network of unmarked dirt roads which branches out across a vast expanse of cork forest. Here sat-nav proved of no use. When, after multiple wrong turns, I finally reached my destination I understood all too well Tamara’s description of the villa as ‘a house where you can feel abandoned.’

The Olgiatis’ principal residence remains the house in the Swiss village of Flims where Valerio grew up and alongside which he later built the studio from which his practice operates. Yet the Villa Além is more than a holiday home. Having equipped it with a server that mirrors the one at the studio, the Olgiatis anticipate spending as much as half of every year there. Motivated by the desire for a more sympathetic climate than alpine Flims has to offer, they initially considered building in north Africa, but were ultimately persuaded by the relative ease of air travel that Portugal was the more viable choice.

Olgiati’s work has always been distinguished by his determination to develop each building out of a single idea. In the case of the Villa Além, it was the desire for a garden − specifically a walled garden that would provide a tempered environment on a site subject to extreme heat and winds. The creation of the house itself was a secondary endeavour, indeed one that Olgiati says he would have dispensed with entirely had it been practical to do so.

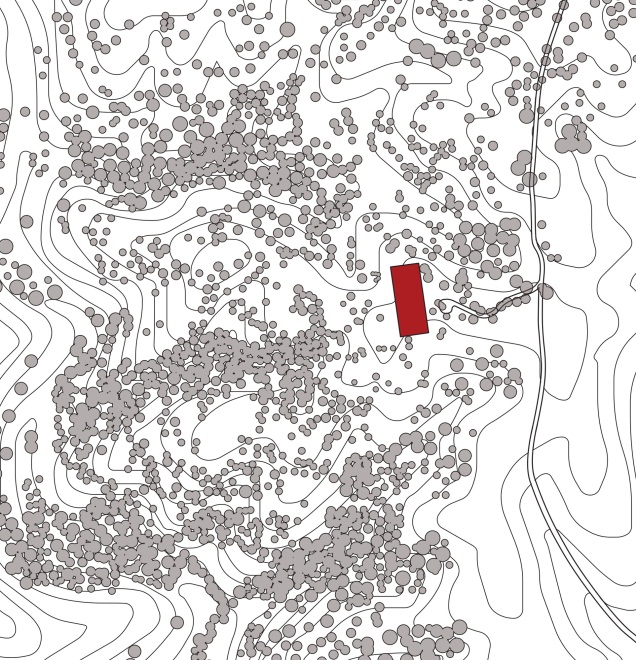

Location plan of Villa Além in Alentejo, Portugal, by Valerio Olgiati

In this radical privileging of external space, the Villa Além belongs to a long line of enquiry in the architect’s work, best exemplified by the 2007 house for the poet and musician, Linard Bardill. Viewed from the street, this building appears to replicate the volume of the barn, which previously occupied its site, but only one third is in fact enclosed, the remainder taking the form of a courtyard that opens to the sky via a large oval aperture. Olgiati has described the Atelier Bardill as ‘a liberated house’ − a liberation, we might surmise, from the shelter’s usually dominant role in the organisation of its site and the rhetorical demands that such a task imposes.

‘The uninitiated could be forgiven for thinking they had stumbled on the temple of a lost civilisation or, to use Olgiati’s analogy, the grounded hulk of Noah’s Ark’

Having purchased a substantial area of land in Portugal, the architect saw the opportunity for his own house to present a still more dramatic imbalance of roofed and unroofed space. Early versions of the plan were developed on the basis of a courtyard modelled on the dimensions of a football pitch. The relatively modest programme of a three-bedroom house was then accommodated around the perimeter, requiring residents to cross the courtyard each time they moved from room to disconnected room. Olgiati had to concede eventually − the plan was fixed only after he had worked his way through close to 100 iterations − that such a vast external space lay beyond two occupants’ powers of inhabitation. However, the model that he adopted in its place was not exactly bijou: the Court of the Myrtles at the royal Moorish palace in Granada, the Alhambra.

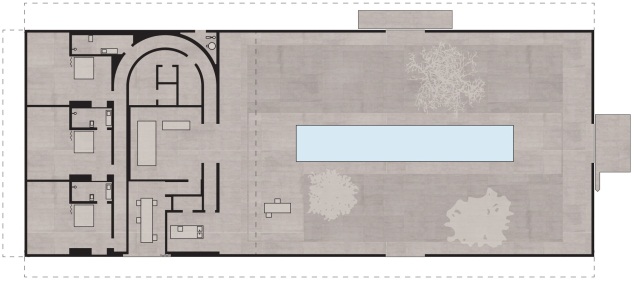

Floor plan of Villa Além in Alentejo, Portugal, by Valerio Olgiati - Click to enlarge

Twice as long as it is wide, this magisterially scaled hortus conclusus is laid out as a series of parallel bands comprising a central pool framed to either side by paths and planting. The long walls are sheer but, at either end, a colonnade provided the sultan and his court with areas where they could survey the scene under protection from the sun. Olgiati’s version, while smaller, retains much of this essential organisation. It has been laid out on a north-south axis with the roofed programme gathered − this time in one place − at the northern end. Comprising just over 20 per cent of the building’s overall area, its relationship to the enclosed external space remains markedly subservient.

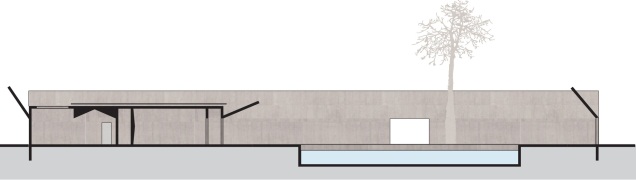

All distinction between the building’s covered and uncovered parts is concealed from the outside world. Emerging into a relatively sparsely forested area, the visitor finds the house nestling beneath a hillock, the top of which provides a level and tree-shaded space to park cars. From this elevated standpoint you are granted a reading of the building’s considerable extent but the predominant impression is one of determined inscrutability. Everything that can be seen is of one material: a rough board-marked concrete of a slightly earthy hue. Describing a rectangle in plan, the perimeter walls rise to just above head height before kicking out at a pronounced angle, rather in the manner of the flaps of an open cardboard box. Casting the wall in heavy shadow, the device lends the building a startlingly monumental character, which Olgiati has consolidated through the very sparing provision of openings. The uninitiated could be forgiven for thinking they had stumbled on the temple of a lost civilisation or, to use the analogy that Olgiati favours, the grounded hulk of Noah’s Ark.

The courtyard is modelled on the Court of the Myrtles in the Alhambra Palace

Only the window to the architect’s office offers a view of the wider world and that is located on the west elevation, well out of sight of the main approach. There are, however, three other large openings, each fitted with a pair of gates that the Olgiatis swing flush to the wall when they are in residence. Each is sited on one of the courtyard’s central axes. Arriving at the one to the east which serves as the principal entrance you therefore find yourself looking across the courtyard and out to the landscape through the equivalent opening in the far wall. The one in the middle of the south wall is also mirrored to the north although in this instance the opening is fitted with a sliding glass door and forms the entrance to the house.

‘Olgiati’s most explicit lift from the Alhambra is a centrally located marble-lined pool − designed in this instance for swimming rather than goldfish’

Section of Villa Além in Alentejo, Portugal, by Valerio Olgiati

The courtyard’s axiality is made more emphatic still by Olgiati’s most explicit lift from the Alhambra: a centrally located marble-lined pool − designed in this instance for swimming rather than the display of goldfish − banded by beds of planting to either side. As the pool anchors the building in the earth so the canted planes crowning the perimeter walls engage it with the sky. Those on the longer walls project outwards − as if following a heliotropic impulse − but on the courtyard’s narrower ends that orientation is reversed, performing a similar role to the Court of the Myrtles’ shaded cloisters.

However, the optimum position from which to view the garden is the cave-like living room that lies behind the central opening in the north wall. Coming in from the often brilliant sunlight it takes your eyes time to adjust to this withdrawn and entirely concrete-formed interior. Positioned at the back is a large in-situ concrete sofa from where the sitter can survey the cinematically framed scene outside. Extending down the length of the pool, through the opening in the far wall and out to a range of mountains rising some 50km away, the vista communicates a vivid sense of your situation within multiple scales of enclosure. In time, the plants that the Olgiatis have introduced will take on a jungle-like density, framing the long view still more closely and transforming the foreground into three pronounced strata: the pool, a belt of head-height vegetation and the angled planes of the perimeter walls rising in brilliant illumination above. But already the garden conveys the captivating impression of a world in microcosm. It makes for a beautiful sight but, through its visual conjunction with the world beyond, a melancholy one too

The rear wall of the sitting room is buckled in section, as if struggling under a great weight

One quality that Olgiati has consistently instilled in the project is a sense of the processional. The long journey required to reach the building contributes to that aim and so too does the use of the courtyard as a transitional space between the entrance and the house proper. However, it is in the elaborately secretive internal planning that we find this impulse most pointedly inscribed. Great lengths have been taken to extend the distance travelled from room to room. Neither the kitchen nor office communicates with the living room directly − as each readily might − but is rather linked to it by a brief tunnel-like passage. The journey from the living room to the bedrooms is even more circuitous. A 40-metre-long corridor heads east out of the living room before essaying a hair-pin bend around an internal plant room and continuing on until it is terminated by the west wall. The bedrooms are single-loaded off an astonishingly labyrinthine passage. All three look out onto their own individual courtyard by way of a wall of full-height glazing. As in the courtyard of the Atelier Bardill, each of these spaces is capped by a concrete slab pierced by a large oval aperture. They are entirely unoccupied save for the discs of brilliant sunlight that travel across them over the course of the day to mesmerising effect.

Olgiati’s aim has always been to make architecture that transcends the particularities of its context, programme and even its moment in history to concern itself with fundamental spatial and structural relationships. Here, working as his own client on a site that is as dislocated as any in Europe, he has found the ideal conditions in which to pursue that quest. Yet, while fundamentalist he may be, a moralist Olgiati is emphatically not. In its mood of lonely, clothing-optional hedonism, the Villa Além looks set to claim a role in the architectural mythology of our own century close to that which the Casa Malaparte enjoyed in the last. The primitive hut has long served as an imaginative lens through which architects have sought to rediscover the discipline’s fundamental principles. Olgiati’s comparison of the Villa Além to Noah’s Ark suggests another. His mysterious, autumnal masterpiece presents itself not so much as Adam’s house in paradise as the home of the last people on earth.

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design